Michael Wilson joined the fire service in 2003 and jumped from hazmat ops to hazmat technician in 2013. At the start of Covid in 2020, he was named hazmat team leader for MABAS Division 10. MABAS stands for Mutual Aid Box Alarm System and is based in Illinois and extends to surrounding states. It functions as a clearing house for emergency response resources that can be deployed where needed. Among its response capabilities, MABAS has 40 hazmat teams and member departments from nearly 1,200 communities.

Describe the type of students you train and the training facilities you use.

At any given time, I manage 45-50 technicians across 16 suburban fire departments just south and west of Chicago. The majority of the team is trained to the technician level, however, we have a good amount of newer techs versus the older guys. We also maintain a normal roster of 10 or so training members that are at the operations level awaiting a tech school.

We have 16 departments within our division to choose training sites within. For the couple of in-classroom training sessions we have a couple of larger departments to choose from but when we look to get suits on and train in the field we have a very large array of sites we use.

How do you mix up the training scenarios so they don’t become predictable or stale?

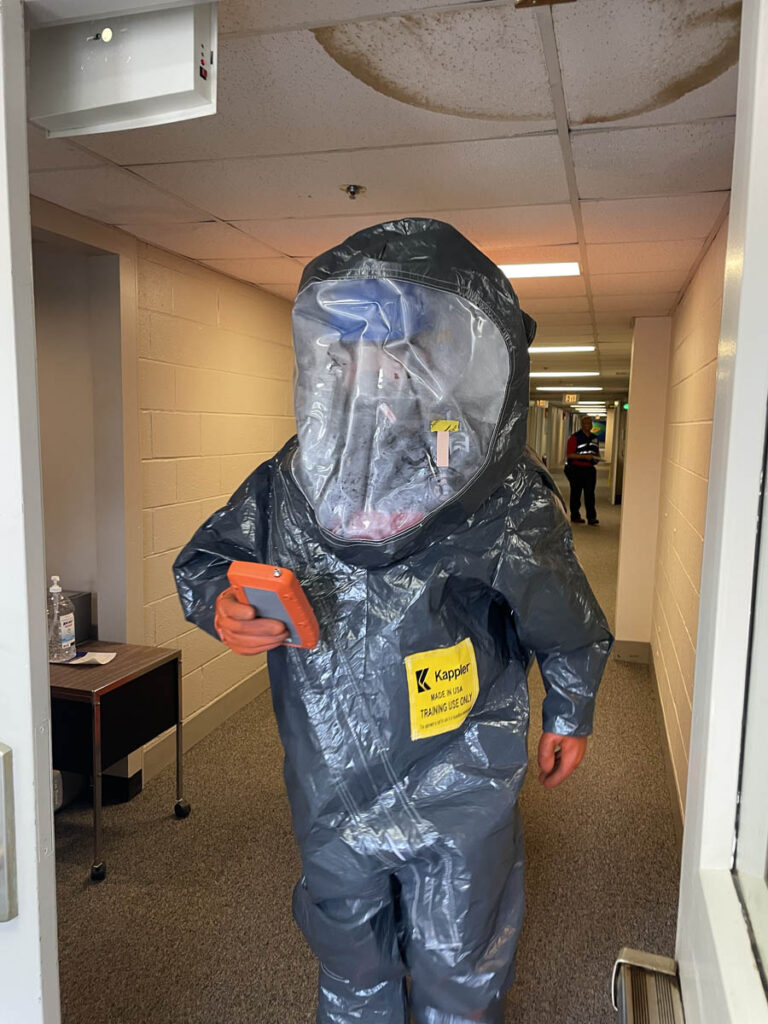

The coordinators and I design our annual plan to cover the basics of being a technician all the way through dealing with more complex situations. We focus on maintaining the basics, but provide different environments to use those skills in. One of the first things I was able to achieve was get most everyone their own training suits. While it may sound silly, when members can perform in their own suit and not have to use one that someone else has been sweating in, it makes them more engaged in the drill. They tend to jump more at the chance to get in the suit.

A lot of our older drills tended to be more standing around talking about what should be done to mitigate whatever the problem may be. We have moved past this and created a variety of new props that forces the team to use their hands on the equipment to mitigate. It is kept light at the beginning of the year. As we move on, we create more difficult environments where they enter in the dark or with the smoke machine going.

Two years ago we simulated a chlorine leak at a water treatment facility with a cylinder using the smoke machine. While it was difficult to operate in the low-visibility environment, the level of difficulty was increased by the grate floor beneath their feet. It took a lot of steady hand work and concentration just to not fumble a tool or bolt into the grates while working in the level A. While it was frustrating for the team, it was a learning experience they took a lot from.

Small changes to the environment being worked in is sometimes huge even when dealing with something that we train on often.

What’s the key to best preparing responders to handle real scenarios outside of the controlled training environment?

I believe that creating unique environments to train in with as many realistic parts to that scenario helps put that in the memory bank, allowing for the techs to pull from it on any given incident. The more we train on the basics, but in unusual ways, the more it makes us aware of our surroundings anytime we are in the suits downrange.

Adding in stairs and obstacles makes them think more thoroughly about what they need to bring and how they are going to get it there. Simply adding some tool boxes on wheels had the team asking if we could move more items to the rolling boxes.

We took the old heavy metal boxes our chlorine and ammonia kits come in and got rid of them for boxes that stack and roll. Life got a lot easier and we didn’t have to rely on large wagons, hand carts or brute muscle in a suit to get from point A to point B.

As I have said, one of the biggest things I maintain through our training is the basics. While we all know them pretty well, the basics are designed to keep us on task and in a manner that we know. Complacency kills. If we don’t dress out the same way every single time, that one time someone forgets they have a key or knife in their pocket they will trip and fall right into a tear in their suit.

While we can’t avoid Murphy’s Law all the time, we lessen the likelihood when we perform those basics the same way every time.

What devices do you rely on most for realistic training?

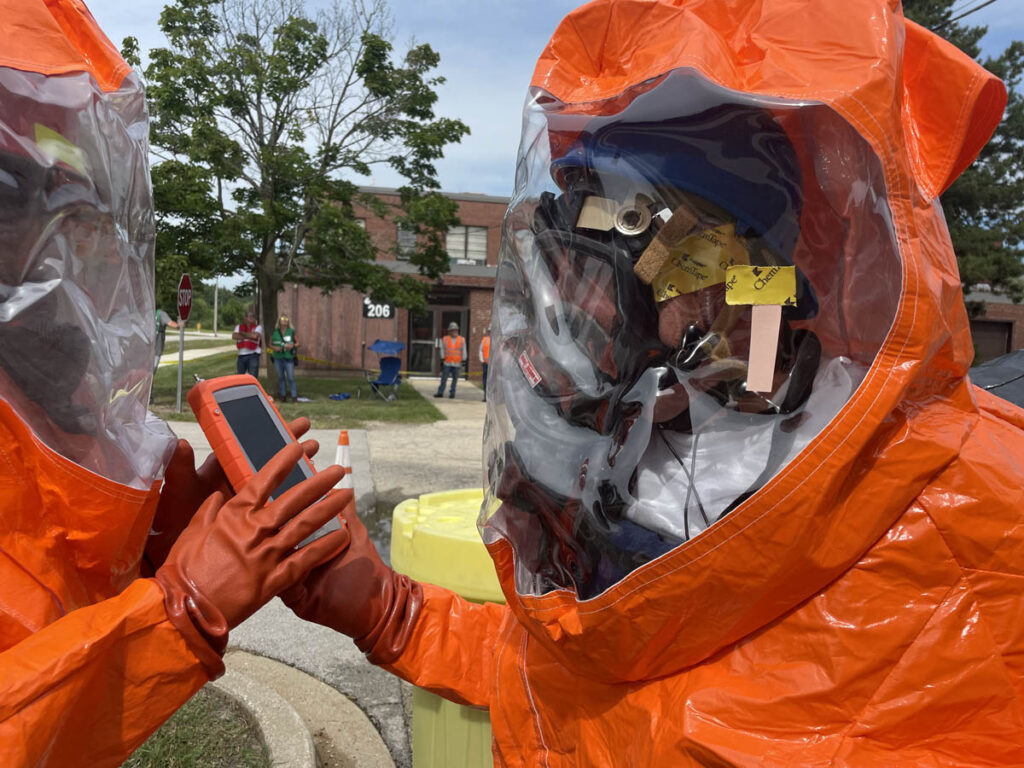

One of the biggest advances into our training was the HazSim. We secured the funds and got our first handheld unit just prior to a large-scale training incident at a federal site this past year. While we still sent our normal meters downrange, having the HazSim alarming in the presence of HF made them think and respond differently on the radio than had someone been standing there telling them what they were seeing. Raising and lowering the values kept them engaged and talking while mitigating the issues.

The first responses from the initial technicians downrange was that this was a game changer and they loved the realism behind it. This coming year we will be working closer with our technical rescue team in a confined space rescue scenario. On the hazmat end, we will mainly assist in the air monitoring. HazSim will play an important role for both of our teams.

While this technology plays a great role in training, if we add too much technology, we will start to lose focus on the basics and rely too much on the screen or whatever that technology may be. If it makes something specific easier, I am all about it, but too much of something isn’t always a good thing.

How, if at all, do you alter training for new responders versus seasoned veterans?

While I believe I am able to keep the training different while covering the basics, those basics can be monotonous and boring. One of the biggest issues in training at this level is enforcing the simple task of dressing out appropriately no matter how big or small the drill is going to be.

If we are going to be in the suits for 5 minutes for a training scenario, we still go through the dress-out sheet in its entirety. I have made it clear that the basic dress out is number 1 and will not be overlooked.

This has been difficult for some of the veterans to deal with. For a time they were just getting in the suits to go get the drill done — the faster they were dressed out, the better it was in their mind. Now some of those veterans have adopted the mindset of taking their time and doing it right, even in drill. It has been a tough sell, but its finally working out the way it should.

How do you keep the classroom portion of hazmat training fresh?

I have been trying to add new things into the training program, such as meeting at our local US EPA facility once a year to go through an interactive review of the incidents they respond to. It’s a unique interaction as they have all the information from the initial responders all the way through their site cleanup. The team really enjoys these reviews and it gives perspective to different mitigation efforts that we may have never considered in the moment.

We only have a couple of classroom settings each year. The EPA is one of those, along with covering science and metering during the cold month of February in the Chicagoland area. It just so happens that one of our team members is actually a full-time EPA employee; he enjoys going through the science and metering with us.

I believe in forging relationships with all levels of response from local, county, state, federal and even private companies. When you involve these different levels in your training, it not only makes your team stronger in response to a real incident but brings in different training levels and viewpoints that makes each a stronger technician. Some of these relationships came out of a large scale dirty bomb exercise this past year. We were forced to work with a MABAS hazmat team we have little interaction with, with bomb squads and with a variety of police departments that we have zero exposure to.