At Incident Ready, Blake McCorkle, CEO and founder, and David Loh, principal — operation manager, are wrestling with how to get hazmat and firefighter training to the next level. Their virtual reality product, Live Simulator, puts incident commanders in configurable, interactive emergency scenarios. Loh and McCorkle sat down with HazSim to discuss how their product came to life and the state of hazmat and fire training.

What inspired your initial idea?

Blake McCorkle: It’s 2014, I think November. I was messing around with a Google Cardboard. I’ve always been a gamer and I was trying to get one of those Call-Of-Duty style games into VR. I figured out how to do it and was immediately killed in the game. My player ragdolls down to the floor and the body laid just in a certain way. I was reminded of a shooting we had run where the patient had laid down similarly — it was an eerie coincidence and it stayed with me. I remember saying, “We should be training using this stuff.”

Over the next weeks and months, I kept coming back to that idea and started looking for VR for first responders. I couldn’t find anything. And it didn’t make sense; this could obviously be useful. The fire service could obviously afford VR — they spend millions on apparatus — and I had hacked together a system using $5 worth of cardboard and a smartphone. I couldn’t get the idea out of my head.

I had always chafed at the way we trained complex skills, like patient assessment or incident command. PowerPoints, protocols, textbooks — they are useful for learning, but not training. You can’t apply what you have learned. It’s like we are trying to learn how to tie a knot by looking at a PowerPoint instead of grabbing some damn rope.

I began to question: Can a first responder, rookie or veteran learn experience? Not every firefighter, police officer or paramedic gets a chance to be first-due or the incident commander at a major incident in their career.

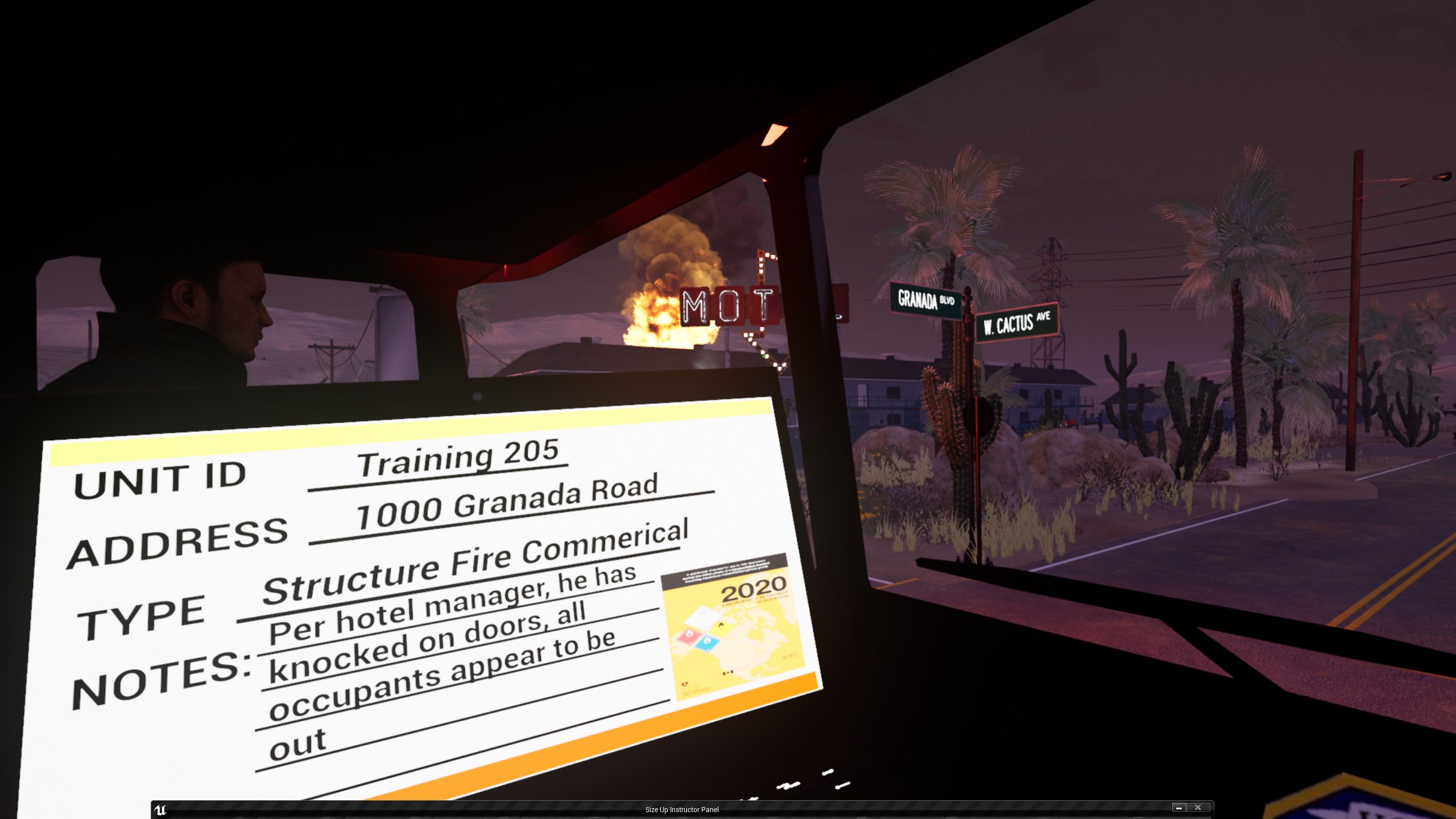

Dave Loh: One day this fire/medic walks into my SimLab. He’s got this huge box and he asks me, “Have you ever used VR?” I told him no. He has this smirk on his face and he hands me this weird looking headset and tells me to take a look. I’m not really sure what to think, part of me wonders am I going to get jumped the moment I put this thing on. Next thing I discover is I’m in the officer’s seat getting dispatched to an incident and then I am suddenly on scene. I was no longer standing at the instructor podium in my SimLab. I wasn’t looking at a screen or a computer. I was somewhere else entirely. I was standing in front of the fire truck, in the middle of the street. One thing that got me as well, I felt the urge to get out of the street, so I wouldn’t get hit by falling debris.

I wasn’t messing with some joystick trying to make some avatars move. I was just there, taking in all that was happening around me. It was simple but a profound difference.

Describe how that idea evolved into what we see today?

Loh: Blake would come to the SimLab from time to time while I was learning VR from another platform that had an extensive learning curve and required the end user three days of training to develop content and action. Then comes Blake, he would show me a few scenarios. And every time I did one, I felt like I had actually been on a scene. It was far more engaging, and it reminded me of incidents I had run in my career. The difference now was that I could go back and really practice performing a good size up as each scenario became more complex. I did not need to spend time developing content, scenarios come built into the software and new content is added with upgrades.

I do remember my lightning bolt moment. One day I was going through one of the hazmat scenarios. I pointed out to Blake something that was a little off in a scenario like, that tanker is unlikely to have been damaged from that kind of collision. Blake nods and says to me, “Yeah, I wasn’t sure. I have no idea. I’ve never run anything remotely like this call.”

That was the wakeup call for me. Because Blake was a career fire/medic. At the time he had like 14 years on, and there were so many calls that he hadn’t seen. I realized we could be putting people in “once in a career” calls on a daily basis. I remember saying to Blake, we don’t have to wait for challenging calls to happen before we gain experience. We can build incidents that have happened before that had firefighter fatalities. He looks at me and says, “Why do you think I started this?”

Blake flipped the idea of a simulation on its head. We would always think of a simulation as this dry, clunky computer thing, right? I’d spend days building content in the other simulation products, and the end result was basically a movie. There was no true immersion or interaction.

Over time we started talking, he would point out things about the state of first responders’ reluctance to welcome innovation, seemingly little facts that actually are pretty significant. Like our SCBA, it was available in 1945 and used by the mining industry. It took 20 years for the fire service to convert from all-service canisters and chemox masks to SCBA, and another 20 years for mandatory-use policies. The fire service is historically slow to accept and adopt new technology.

McCorkle: This “refusal to breath” phenomenon is why I abandoned looking for investors for funds to hire developers, and instead began learning development myself. What kind of investor would become involved in an industry where people didn’t even care about something as vital as breathing? We saw how the military can train an 18-year-old Marine to make split second life-or-death decisions by using virtual reality. Kids today have experienced quality realistic gaming software, so why can’t this technology be introduced to first responders?

We’re done waiting for the problem to just magically be solved. We are solving the problem. And while it’s like rocket science to try to learn game development, the actual experience inside is very simple — you are on scene. The size-up is one of the most critical parts to any call (particularly in hazmat) and yet it’s one of those skills that can be mastered without relying on, well, just waiting for the calls.

The end users do not need to learn how to be content developers. They can open the box of hardware with the software installed, plug in the components, and start providing first responders with experience.

Loh: Blake had warned me that we were taking too long to answer this question. I told him that this answer was a long time coming. There are so many aspects of the fire service and its vendors that I’ve sort of woken up to, like that vendors don’t often have a price easily available. Why is that? We know the reason, so they can charge one department more than another. That makes no damn sense.

What did you learn from early failures?

Loh: Simulation software developers promised us everything until we owned the product. We found this to be a raw deal and felt this was a disservice to us and the first responder community. There was a definite sense of taking the money and running.

McCorkle: There are some truths about the fire service, about how progress happens, that I thought would be much more obvious than they really are. I thought the first time I showed the product off, there would be this “Yes, of course!” reaction. But what I thought was a necessity, was seen as a novelty. Part of that is to be expected; it took us 40 years minimum to adopt SCBAs.

One of us (first responders) was going to have to learn this stuff, game engine development I mean. it’s one thing to say, “Okay you need to make the firefighters deploy the hose” and another to know that you need to spawn a spline mesh at an angle perpendicular to the tangent of the shoulder socket. So, the development takes time, not just for a learning curve to actually implement features, but to actually understand what features are important. A lot of times you won’t know what those are until you try them out.

My mistake was not accepting this reality sooner. To be honest, I never wanted to have to learn any of this. I ignored something, for a long time, and it made things much harder. I should have accepted the reality that I was going to have to learn how to build this entire thing. The few companies that have managed to sneak their product into a fire station, partly because training officers have so few choices, have quite frankly pissed me off. We have a paramilitary style job, but with a Boy Scout budget. Yet they will sell you a laptop at twice the price of something you can go to Best Buy for.

What has been the most profound story you have heard from a customer?

Loh: One customer stated they have seen a few simulation products. It wasn’t until they had experienced the Live Simulator and heard how the participants sounded on the radio by activating the recorded playback, saw the high-quality graphics, had the ability to have customized benchmarks and a simpler user-friendly set up it was truly a learning experience for a seasoned veteran with a positive outcome.

McCorkle: I had taken the simulator to an academy officer at my department. We had enough slots so our training captain allowed some non-officers to attend. I was instructing one of our personnel who had only two years on, basically someone who was more rookie than veteran. He had no fire officer training classes, no command training. And it wasn’t someone who was some command badass either. I didn’t realize it at the time but what became obvious was this person was a perfect test subject. He was essentially a blank slate.

The first scenario was a stuttering mess. This was expected. Again, the guy hadn’t had any command training whatsoever. But I gave him a quick primer with the advice, just tell me what you see; don’t worry about jargon. Over the next 40 minutes, I watched this guy get into his rhythm. I was telling him less and less each scenario. By the end, when I would hear him performing a size up against our other experienced officers who had been 10 years on the truck, the difference was much less. You could still tell the veteran from the rookie, but the gap was much smaller. I realized that, in some ways, he had gained years of experience in under an hour. It wasn’t planned at all, but I proved how effective the Live Simulator’s impact had as a training tool.

What problem keeps you up at night?

Loh: Knowing there are thousands of first responders who have hours of classroom knowledge and PowerPoint-delivered training. I wonder how effective they will be with command and controlling a scene due to their lack of experience.

McCorkle: Two issues. One, we have a fragmented industry, and the fire service is, roughly, 1,217,000 fire service personnel, 70% volunteer, 28,000 individual departments. There are about 50,000 fire stations, each has its own unique demographics — the politics of the city or county. And this blends into the second problem. We have a disjointed customer base. The people who use our product are not the ones who actually purchase it, a chief does or a training officer does. Again, that person has their own agency’s politics that affect their purchasing ability.

What does the near-term future hold for the company and products?

McCorkle: We’ve got to put people in this thing. VR is one of those technologies that you don’t really appreciate until you use it, and it’s hard to convey this to people who’ve never experienced it. Part of this is the sensations, like your depth perception, is all lower-brain, all unconscious. You don’t have to try to feel or imagine being somewhere, you are just there.

It’s obviously self-serving of us to say that our product is a necessity, but we’re already passed the point that we can comfortably state it’s irresponsible to not train with this. But you can look at so many developments in the fire service that used to be novelties that are hard set requirements. Years ago, if MSA or Scott told you that you should all be using SCBAs, they would have a vested interested, but they wouldn’t have been wrong.

Loh: Simulation is a product that has been used in Europe and Asia for 10 to 15 years now. Recently it has had a limited presence in the USA and Canada. Products like Live Simulator’s, Run The Call, Pump Simulator, Escape From Fire and HazSim have made training much more engaging and immersive. We see rapid growth by creating a product that puts technology in the hands of the trainee that generates a pulse, self-evaluates, and develops the trainees analytical thinking skills while sizing up a scene or taking in situational awareness.

McCorkle: No more 5/5 bullshit training guys. Put on the headset. You’ll see.

What does the long-term future hold for the company and products?

Loh: We are currently building Module 2, Incident Command, developing scenes for law enforcement, EMS algorithms, hazmat, and special operations.

McCorkle: I’ve been developing the assembly line for experience. Without going down that rabbit hole here, let’s just say there is a way to take someone’s experience and replicate it for mass distribution. My goal is to take some of our senior leadership, men and women who have responded to complex incidents that I’ve not even considered, and preserve their experience for posterity. These are hard-won lessons that often-cost lives to learn. But if I take those and share them with all of us, how much higher can our abilities go?

Any predictions on how hazmat response and training will change in the coming years?

Loh: Currently, there is not enough required hazmat training hours, and the number of hours is inconsistent across the board. OSHA 1910.120 (q) and EPA 40CFR311 requirements for operational level responders is being ignored by many agencies. Confusion exists with the awareness level responder versus operations level responder. Refer to NFPA 472 and future NFPA 1072. Agencies who purchase and issue air monitoring devices suggests that agency meet the requirement of operational level responder-mission specific 6.7 including 6.2, 6.3, 6.6, and 6.8.

Simulation along with hands-on exercises involving tools and props can be very effective with certification training and recertification for hazmat response for industrial inside the gate and outside the gate hazmat responders.

McCorkle: Another unexpected benefit of VR is being able to take your city manager, finance director, county commissioner, basically the person who oversees your budget, and literally throw them to the fire. You can put them on scene and let them see just why you are requesting that new fire engine. Imagine them standing outside and watching for minutes while the fire grows on a two-story ranch with taxpayers outside demanding to know where is the fire department because the engine broke down, but you cut the new engine out of the budget. This is particularly relevant for hazmat. When you have a discipline that can be a foreign language even to fellow firefighters, just how are you going to justify those expenses to a layperson on your city council? We all know the term industry standards only goes so far.

On the training front, I think there’s going to be more hybrid exercises — ones that combine non-touch simulation, like VR, with traditional physical props. Having a better understanding of what type of skills you are training — for example being able to recognize different hazardous components and prioritize and triage the most critical ones — you can learn that entirely in VR. Then you can blend this with staff in the real world who move to mitigate the physical task. The benefit is that the setup and organization of this is made much easier by having the main command elements appear in VR. The scene is loaded instantly and can be cleaned up even faster. You will still need to suit up and work with your tools (anyone who says otherwise is suspect in my opinion).

This is why firefighters are able to tie knots on an incident, even though they practiced tying them in the bay or even in the recliner. The setting matters for some skills, but for others, the setting doesn’t matter. Experience is just a collection of patterns, of what you see, hear, and feel. When you are tying a knot, the feel of the rope matters, not the color of the floor. For managing hazmat scenes, you don’t need to feel heat or smell toxic fumes, you need to be able to see all the details of a scene and filter out the critical ones.

What do you see in the hazmat world that gives you the most concern?

McCorkle: I’ve mentioned this to Dave on many occasions: large-scale MCIs and the effect that has on our communications is what scares me the most. One of the biggest problems we have is coordinating these large-scale incidents. And if anyone is particularly passionate about this and recognizes the problem, I will consult with anyone, for free, on how to develop a program that lets multiple agencies train on managing a large-scale incident. My concern for this is more related to just large-scale incidents in general but the hazmat factor just makes it 10 times worse. I can’t imagine how many times the original substance gets changed through the first hour of what they are really dealing with.

Loh: The lack of knowledge or the perceived knowledge to make a good hazard and risk assessment prior to the arrival of a hazmat team gives me the most concern. You don’t need to be a technician to assess the hazard and the risks.

Operational level responders who lack the knowledge of ID and recognition, the ability to read and understand physical and chemical properties from NIOSH, SDS and the DOT’s action guide identifying potential hazards, public safety measures and emergency response priorities.

Lack of training in PPE selection where structural protective clothing and SCBA may be appropriate for a quick rescue, understanding metering, vapor control measures, emergency decon and the tools to make a good hazard and risk assessment are all concerning.

What in the Hazmat world gives you the greatest sense of optimism?

Loh: Having technology available to train with Live Simulator, meter simulation with HazSim, Pre-Incident Plans/Hazard and Risk with Visual Plan and Plume Mapping.

McCorkle: I’m not selling them, but I think we underutilize drones greatly in the fire service. The FAA is probably the biggest hurdle to this, but it is getting better.